Can Self-Interest Save the World?

The world is a naturally simple and beautiful place. Then we come along and screw it all up by thinking far too much about it. I was reminded of this truism recently when discussing Game Theory with my 13 year-old daughter. And if anything will remind you that you’re thinking way too much, it’s a 13 year-old.

Game Theory, in a preposterous oversimplification that will make said 13 year-old roll her eyes in melodramatic disapproval, is a series of mathematical models involving strategic interactions amongst reasonable and self-interested agents. And if that last sentence wasn’t enough to make your eyes glaze over and have you click onto a different Medium article, buckle in, my friends, ‘cause shit is about to get seriously nerdy up in here. And that’s when TRUTH gets really good.

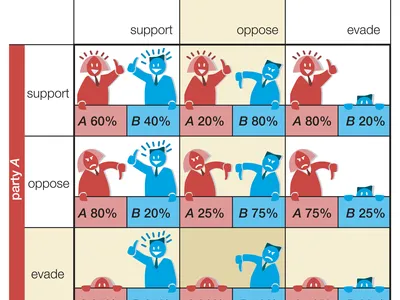

Game Theory predisposes a particular set of circumstances and then predicts how the various players will behave given the reactions of others around them. First and foremost, game theory scenarios assume two things about all potential human participants: that they be rational and that they be guided by self-interest. Now, anyone who assumes human beings will act rationally clearly hasn’t met Marjorie Taylor Greene, but let’s go with this one for a moment. The self-interest part we will come back to in a moment, for it is there that the entire fate of humanity rests.

One of the more famous scenarios in Game Theory is the Prisoner’s Dilemma, described by William Pounstone in his 1993 book of the same name as:

Two members of a criminal gang, A and B, are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of communication with their partner. The principal charge would lead to a sentence of ten years in prison; however, the police do not have the evidence for a conviction. They plan to sentence both to two years in prison on a lesser charge but offer each prisoner a Faustian bargain: If one of them confesses to the crime of the principal charge, betraying the other, they will be pardoned and free to leave while the other must serve the entirety of the sentence instead of just two years for the lesser charge.

If this scenario sounds vaguely familiar, a version of it appears in the film The Dark Knight as the Joker stows explosives on two boats and gives each the detonators to blow up the other before the other boat can do it to them. If neither acts, both boats explode after 10 minutes. In both of these cases, it is rational for both parties to act in their own self-interest and betray the other, even though the best collective result in the Prisoner’s Dilemma is mutual cooperation where each of the prisoners gets just two years instead of anyone getting ten. After all, Batman is not always there to intervene.

Game Theory is often used as a series of predictive scenarios in order to anticipate how other nations or military opponents might react given a particular set of circumstances. But while these hypothetical scenarios might just be shits and giggles when being done by abstract thinkers in a hypothetical world, we often witness them playing out before us on the stage of global affairs.

Which brings us back again to those words “rational” and “self-interest”. Don’t take them lightly. For in the worlds of Game Theory, and perhaps even in our real world, they are what keep us from complete annihilation. In an era of nuclear proliferation, where eight different countries now possess the capacity to detonate nuclear arsenals, what maintains the peace is the assurance of mutual destruction, the idea that if we blow you up, you’re going to blow us up too- sort of like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, but with nukes. It is in our self-interest, and that of every other nation not to use nuclear weapons lest they be used against us.

18th century Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith once suggested in his book The Wealth of Nations that self-interest functioned similarly in creating a healthy free market economy. Through self-interest, we all will act in accordance with that which serves us most, which inherently also serves to better the community around us. The result is an economic and practical win-win that benefits both the actor and the society at-large. But not all moral dilemmas are quite this easy.

For decades now, scientists have been warning us that we are running out of time to solve the global climate crisis. Let’s just assume that most of us are intelligent human beings who understand that climate change is a serious threat to our continued existence. After all, Game Theory presupposes that people are “rational” human beings, not FOX News viewers. Self-interest would dictate that we need to act cooperatively in order to escape the doom awaiting all of us. Nothing is going to matter if we don’t have a planet to live on. But again, self-interest is not so simple.

Each country, feeling betrayed by the lack of response from others, waits for everyone else to commit to more drastic plans of action. In the United States, we point the finger of environmental morality at China and India and cite that as support for our decision to back out of international climate accords. Corporations, meanwhile, continue to dump toxic chemicals into our water and air as the fossil fuel industry lobbies Congress for even further drilling and reliance on the petroleum products that are causing the ozone-depleting emissions. Even we as individuals opt far too often to increase our carbon footprint knowing what it means for our environment but shrugging our shoulders and going “What can just I do?”

The answer, of course is a lot, but only if we do so collectively. That requires that we see beyond the immediate and recognize the impending annihilation of the human race encroaching ever quicker upon us. It requires that we take the longview of loving embrace to our planet rather than the hummer in the alleyway of personal profit. We must learn to work together to avoid our own mutual destruction because destroying the planet for monetary gain isn’t in any of our own self-interests.

Steven Craig is the author of the best-selling novel WAITING FOR TODAY, as well as numerous published poems, short stories, and dramatic works. Read his blog TRUTH: In 1000 Words or Less every THURSDAY at www.waitingfortoday.com